Trade mark requirements and how to use trade marks properly

In order to understand how to use a trade mark properly, it is important to understand how a trade mark works commercially and legally.

Commercial operation of trade marks

Every time that a customer has a customer experience with your goods or services, this generates a small amount of ‘reputation’. This reputation attaches to the trade mark and branding.

If the trade mark is distinctive, it will be ‘sticky’ to the reputation, allowing the reputation to stick to it. If the trade mark and branding are not distinctive, that customer will easily forget the trade mark or branding, and a portion of the reputation will fall away. The value of the trade mark and branding becomes increased as more reputation attaches to them.

Trade marks and branding that allow the reputation to stick to it will build up in value quicker; by contrast, those that are not sticky, allowing reputation to fall away, will struggle to build in value. When enough value builds up in the trade marks and branding, these can become major capital assets of a business.

The stickiness of a trade mark is directly related to its distinctiveness. The sole ‘reason for being’ of a trade mark is to distinguish your goods or services from those of your competitors. When your trade mark is descriptive or semi-descriptive of the goods and services that you are selling, then your mark is not distinctive because the ordinary use of descriptive words by your competitors (in describing their own product) will be diluting your trade mark.

In addition, It is typically easier to register domain names and social media accounts for distinctive trade marks rather than for descriptive ones. Another reason why you should use a distinctive trade mark is because, if you use a descriptive or semi-descriptive trade mark; if a customer performs an online search, they will almost certainly retrieve your competitors’ products as well as yours.

In addition to the commercial reasons, there are legal reasons why you should not be using a descriptive or semi-descriptive trade mark.

Registered trade mark applications

When a trade mark application is filed, it is filed under a particular class of goods and/or services, together with a specification of goods and/or services that your trade mark is being used on or is intended to be used on. The trade mark itself is not allowed to be descriptive of goods included in that class of goods or services.

For example, if I were a grocery store owner, I would want to file a trade mark application in a particular class and with a specification of goods or services relating to ‘fresh vegetables’. Class 31 includes ’fresh vegetables‘ (if you are growing them), and class 43 relates to ’services for providing food and drink‘ (if you are selling them).

In such a case, I would have trouble registering the trade mark “banana” in these classes as it is descriptive of the goods or services in these classes. This is because, if the trade mark “banana” were allowed to be registered, my competitors (i.e., other grocery store owners) would not be able to advertise their goods in the ordinary course of trade without infringing my trade mark. Clearly, this is would not be acceptable, and my trade mark application would be refused.

The general rule of thumb is that you would not be able to get protection for a trade mark that your competitors would reasonably expect to use in the ordinary course of trade.

Levels of distinctiveness

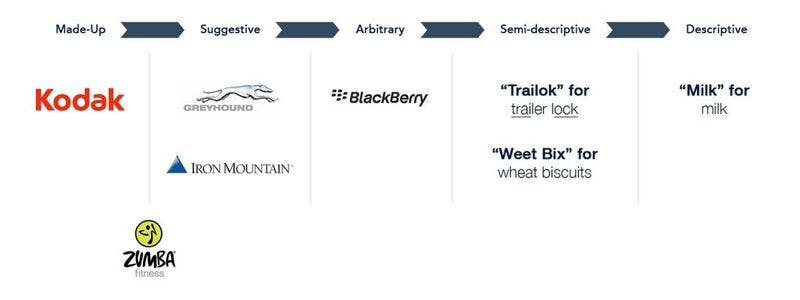

Trade mark attorneys typically recognise various levels of distinctiveness (on a sliding scale). We describe five different levels of distinctiveness from best to worst with reference to the figure below, and taking both legal and commercial factors into account.

1. Made-up trade marks

The best and most distinctive trade marks are those that have been made up. Examples of made-up trade-marks include Kodak, Xerox, and Zumba. These are inherently distinctive and offer the added benefit of the low likelihood of somebody else making up the same trade mark and filing it in the same class of goods and services. It is also relatively easy to find associated domain names and social media accounts for made up trade marks.

2. Suggestive trade marks

The next level down are suggestive trade marks. These are suggestive of the qualities that you’re trying to get across, but are not descriptive of the goods or services. Examples of suggestive trade marks include Greyhound for bus services (suggestive of speed and sleekness) and Iron Mountain for data storage (suggesting security, immovability, and impenetrableness). Actually, Zumba for exercise classes is another suggestive trade mark in that it is suggestive of Samba.

3. Arbitrary trade marks

The next level down are arbitrary trade marks. These are typically existing English words that are filed in a class that they are not descriptive of. Examples of these include “Blackberry” for mobile phones, and “Google” for search services (yes it is an English word!).

4. Semi-descriptive trade marks

The next level down in terms of its commercial effect are semi-descriptive trade marks. An example of a semi-descriptive trade mark is the word ‘Trailok’ for a trailer locking product. Even though it would probably be registrable, the ordinary use of the word trailer lock by your competitors would be diluting your trade mark, and being semi-descriptive, it would not be sticky to reputation.

5. Descriptive trade marks

The next level are purely descriptive words, such as “Milk” for milk; these would never be protectable as a trade mark, and a customer of yours could actually go as far as buying your product while wondering whether it’s your competitors’ product!

If you have any queries about your trade mark or how to get protection for your trade mark, please feel free to call one of our trade mark experts at Baxter IP.