Things to think about in commercialising your idea

When inventors come up with new ideas, they are typically full of drive to see their invention in the marketplace and preferably making money for themselves. But pretty soon, inventors find out that there is a lot to learn in the commercialisation process. This article talks about some (but not all) of the things to consider in taking an invention to market.

Types of commercialisation

One of the first things you need to consider is how you intend to go about commercialising your idea. One form of commercialisation is to file a patent and/or design application and sell the intellectual property outright to a buyer (for example, a large manufacturer). In this scenario, the buyer will own the intellectual property and you will be left with no residual rights to the intellectual property.

Another form of commercialisation involves obtaining intellectual property protection and then licensing the intellectual property to a licensee. In this scenario, you will retain ownership or control of the intellectual property and the licensee will pay you for the right to manufacture products that are protected by the intellectual property, or which may be protected by the intellectual property in the future.

You should keep in mind that a licensing scenario should be a win-win situation for both parties, as not only will the inventor/designer be receiving license royalties but their intellectual property will also be providing a benefit to the licensee. The benefit may be in preventing the licensee’s competitors from competing with them or in offering the licensee an additional product offering for their product lines.

Both of the above two types of commercialisation involve relatively low risk by the inventor/designer since the only costs involved are the costs of obtaining the relevant intellectual property.

Another form of commercialisation is “deployment”, where the inventor/designer goes to the trouble of having the product fully engineered for manufacture, sets up the manufacturing, pays for the stockholding, sets up distribution and actually sells the products to the intended market. This form of commercialisation involves the most effort, time, cost, and risk. However, it also typically results in the inventor making the most profit.

When the inventor has commercially useful intellectual property, they may be able to negotiate a combination of deployment and licensing with a manufacturer. For example, they may license a manufacturer to manufacture and distribute a product in certain territories and/or industries, while reserving other territories and/or industries for deployment by themselves.

It doesn’t matter how you intend on commercialising your invention, it will be assisted by having commercially useful intellectual property in place.

Putting together a business plan

Even if you are considering licensing or selling your intellectual property to a third party you will most likely need to put together a business plan.

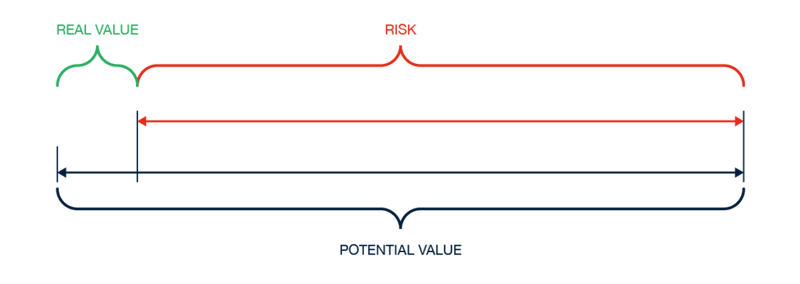

This is because when an invention is just an idea in an inventor’s head it represents potential value. However, the potential value is almost completely offset by risk, making the current actual value relatively low. This is illustrated below:

The risk is created by having a wide variety of unanswered questions around the invention. These questions can be broadly separated into four different groups.

Technical proof of concept

These kinds of questions relate to how and if the technology works, and can include:

- How is it to be manufactured?

- What is it made of?

- Does it require assembly?

- Where will it be made?

- Does it work?

- Does it do what you say it can do?

- Does it require fabrication?

- Does it require moulds?

Business and monetisation proof of concept

These kinds of questions relate to the cost implications for each of the answers to the technical questions above, as well as to other questions listed below. Examples of these questions include:

- How much is the raw material cost?

- How much is the assembly cost?

- How much is the freight cost?

- How much are the mould costs?

- How much is the manufacturer’s markup?

- How much is the wholesaler’s markup?

- How much is the retailer’s markup?

- How much is your premium?

- How is the invention going to be commercialised?

- What are the marketing costs?

- What are the patenting costs?

Market proof of concept

Examples of these include:

- What is the size of the market?

- Where are the main markets?

- What are the main competitors in the marketplace?

- What size market share can your invention take?

- How are your customers doing things right now?

- How much will cost affect the market size and market penetration?

- What is the most suitable price point for the product?

Intellectual property proof of concept

Examples of these questions include:

- What form of intellectual property will be most suitable for protecting my idea?

- What scope of protection can I get for my product in each different type of intellectual property?

- Can I get multilayered intellectual property protection?

- How can I make sure that I retain control of the invention/design during commercialisation?

You will notice that, as one of the proof of concepts change, it will affect the answers of the others. You may need to iterate through the questions a few times before changing one so that it does not change the others too drastically.

Answering the questions above may require you to do research by enquiring with manufacturers/designers/marketers and may require you to do some form of market validation (while keeping in mind the novelty requirements for patentability and design registration).

The more of these questions are answered, and with the increased accuracy of the answers, the risk is reduced and the real value starts crystallising out of the potential value. When a business plan is produced from this information and presented to an investor or licensee, they will be able to see the real value in the invention more clearly and will be more likely to pick up the ball and run with it.

If you have any questions about commercialisation and how intellectual property may be able to help you in commercialising your idea, please feel free to come and speak to one of our patent attorneys.