A purpose or a promise: Utility in ESCO Corporation v Ronneby Road Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 46

Esco Corporation (“ESCO”) was the applicant for Australian standard patent application no. 2011201135 entitled “Wear Assembly”. Paragraph 1 of the application provides that the invention “pertains to a wear assembly for securing a wear member to excavating equipment”. At paragraph 3, the Specification states that “wear parts are commonly attached to excavating equipment, such as excavating buckets or cutterheads, to protect equipment from wear and to enhance digging operation”.

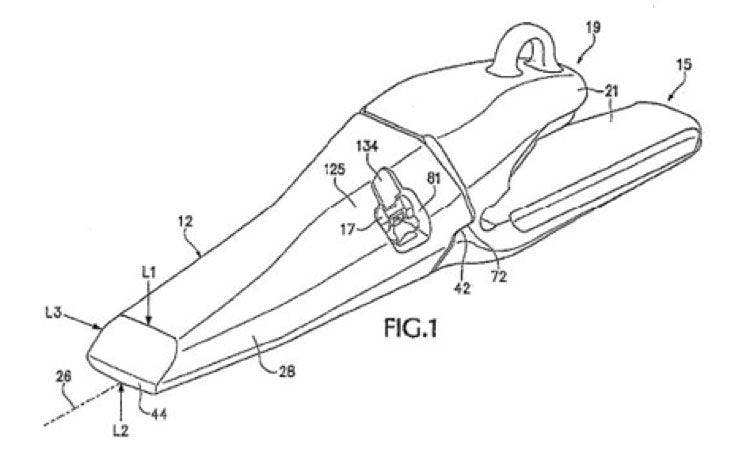

Below is shown Figure 1 of the drawings, illustrating a wear assembly having a base (15) with two rear legs (21) and a wear member (12) placed on a nose of the base (15) and attached thereto.

A first group of Claims in the application defined a wear member for attachment to excavating equipment, while a second group of Claims defined a wear assembly for excavating equipment, including a wear member.

Specifically, independent Claim 1, in the first group of Claims, defined:

“A wear member for attachment to excavating equipment comprising a front end to contact materials being excavated and protect the excavating equipment, a rear end, a socket that opens in the rear end to receive a base fixed to the excavating equipment, a through hole in communication with the socket, and a lock integrally connected in the through hole and movable without a hammer between a hold position where the lock can secure the wear member to the base and a release position where the wear member can be released from the base, the lock and the through hole being cooperatively structured to retain the lock in the through hole in each of the said hold and release positions irrespective of the receipt of the base in the socket or the orientation of the member.”

Independent Claim 19, in the second group of Claims, defined:

“A wear assembly for excavating equipment comprising a base fixed to the excavating equipment and a wear member having (i) a wearable body having a wear surface to contact materials being excavated and protect the excavating equipment, and a cavity to receive a base fixed to the excavating equipment, and (ii) a lock integrally secured to the wearable body for movement between a hold position wherein the lock engages the base to hold the wearable body to the base and a release position wherein the lock permits installation and removal of the wearable body on and from the base, the lock being secured to the wearable body in both the hold and release positions irrespective of whether the base is in the cavity or the orientation of the wearable body.”

Importantly in relation to the issue of utility, paragraph 6 of the Specification states that “[t]he present invention pertains to an improved wear assembly for securing wear members to excavating equipment for enhanced stability, strength, durability, penetration, safety and ease of replacement”.

At first instance, Ronneby Road Pty Ltd (“Ronneby”) argued that each and every stated advantage in paragraph 6 was a promise to be fulfilled by each and every Claim. ESCO, on the other hand, argued that the advantages were not promises but rather purposes or advantages of a general want, as indicated by use of the term “pertains to” in paragraph 6. Instead, ESCO contended that aspects of the invention described in paragraph 15 of the Specification were the true source of the promise.

Paragraph 15 of the Specification provides, “[i]n one other aspect of the invention, the lock is integrally secured to the wear member for shipping and storage as a single integral component. The lock is maintained within the lock opening irrespective of the insertion of the nose into the cavity, which results in less shipping costs, reduced storage needs, and less inventory concerns.”

Also relevant was paragraph 16 of the Specification, which provides, “[i]n another aspect of the invention, the lock is releasably securable in the lock opening in the wear member in both hold and release positions to reduce the risk of dropping or losing the lock during installation. Such an assembly involves fewer independent components and an easier installation procedure.”

The Primary Judge considered that the six stated advantages in paragraph 6 of the Specification constituted six promises, each and every one of which was required to be attained by each and every Claim. Given then that none of the Claims were considered to achieve the promises of enhanced strength, durability, or penetration, the Primary Judge found that the promised result was not delivered by the invention as claimed, leaving all Claims lacking in utility.

On appeal, the Full Court considered that any promises of the invention should be derived from considering the Specification as a whole, including the Claims. At paragraph 303 of decision, the Full Court provides that “it may well be necessary to turn to the body of the Specification, then turn to the claims, and then turn back to the Specification to identify what degree of symmetry exists between the subject matter of the claims (for example those relevant to the wear member only) and the paragraphs of the Specification which contain the promise relevant to those claims”. It was pointed out that paragraph 6 of the Specification referenced only the wear assembly and not the wear member, to which an entire Claim group was directed.

On reviewing the Specification as a whole, the Full Court determined that the true promise of the invention was found in paragraphs 15 and 16 of the Specification, as these paragraphs contained the only aspects of the described invention relevant to Claim 1. As Claim 1 did achieve the promises set out in paragraphs 15 and 16, it was found to be useful and therefore valid.

Finally, although it was accepted that paragraph 6 of the Specification did not provide the relevant promise of the invention, in the alternative event that it did, the six stated advantages were not to be considered as a composite promise (as the Primary Judge did). Rather, the promises were to be read disjunctively across the full set of Claims, with any Claim achieving any one of the six promises being considered useful.