Patent-eligibility of "business methods" – no longer business as usual

Recently is has become difficult if not impossible to patent “business methods” in Australia. Such is evident from the large number of “business method” patent applications being refused by the Examiners and Delegates at IP Australia.

This article is addressed to patent applicants and practitioners involved in patenting “business method” patents, these often being patents relating to computer implemented methods and the like, and sets out the current arguments used by IP Australia in rejecting applications, our opinion as to whether these arguments are lawful and tips to avoid refusal.

Australia used to be a safe haven for “business methods”. For example, in the rare instance of a method claim being rejected by an Examiner, the appropriate response was to insert the words “a computer implemented method” into the preamble of the claim to overcome the objection. I quote from well respected Patent Attorney Blog that notes “Until recently, our advice to clients was that business methods were patentable in AU, provided that the claims were limited to execution of the business method in a computer environment”

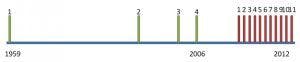

What is now apparent however is that policy considerations at play within IP Australia now hold “business methods” to be ineligible for patent protection. Such is clearly apparent from the below timeline showing the court decisions[1] on business methods in green and the recent tranche[2] of Patent Office Decisions refusals.

Such a stance would appear unwarranted as there has been no change in law. In fact, as is evident from above, the last court decision on the topic of patent eligibility of business methods was Grant[3] in 2006.

Such a practice by IP Australia is unfortunate as legitimate technology is being ‘caught in the crossfire’ and being refused under the current practice. For example, Google’s ad serving network which nets the company upwards of $11 billion annually is a case in point. Despite the clear economic indication of inventiveness, a claim to a method of serving an advert may well face refusal for being a “business method”.

A summary of the current IP Australia Practice

The current Examination practice of IP Australia (as of mid 2010) can be summarised by the following approaches taken by Examiners:

No more “tech washing”

Here the Examiners assert that you cannot simply make a patent ineligible invention patentable by simply including a computing device or the like into a claim.

Technical integers are “merely incidental”

Here Examiners remove computer apparatus and other technical integers and examine whether what remains (i.e. the ‘core’ of the invention) is a business method.

For example, below is a real example of a refusal we received in response for an International-type search wherein the Examiner opined that:

All the steps involved in the current invention are all directed to a mere business scheme or presentation of information. The use of computer to store data, generate message, encrypt and decrypt data is considered to be ‘incidental or indirect’ use of the computer and does not change the core of the invention which is a business scheme or presentation of data. Therefore, I believe the current application contains no patentable subject matter under the PCT or under the Australian national grant procedures.

Incidentally, despite refusing to perform the search, IP Australia will only refund $700 of the (then) $1,400 fee.

Substance over form

Here Examiners assert that rather than consider the claimed invention, it is proper to examine the essence (or the “Vibe”, an approach used by Dennis Denuto in the film ‘The Castle’ to interpret the Australian Constitution) of the patent specification.

Such an approach is the “substance over form approach” and was first put forward by the Delegate inResearch Affiliates[4] as:

The application disclosure should be considered as a whole and care should be taken not to allow the form of words used in a claim to cloud the real issue of manner of manufacture.

Light at the end of the tunnel

We note however that we’re not the only patent attorney to disagree with IP Australia’s practice and thankfully at least one of the above IP Australia decisions is being appealed to the Federal Court. This case is the abovementioned Research Affiliates case set down for hearing[5] on 26 November later this year.

We, as do other Patent Attorneys, expect that this case will reverse the current practice of IP Australia and will reiterate that there is no patent ineligibility for business methods per se.

Until such time that the Research Affiliates, LLC case is heard, let’s consider what the law says about whether a “business method” is patentable or not.

The Patents Act

Referring to the Patents Act 1990, Schedule 1 defines “invention” as “any manner of new manufacture the subject of letters patent and grant of privilege within section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies, and includes an alleged invention”. Furthermore, Section 18(1)(a) states that “a patentable invention is an invention that, so far as claimed in any claim is a manner of manufacture within the meaning of section 6 of the Statute of Monopolies.”

By “manner of manufacture” does it follow that something is only patentable because it is manufactured, something tangible or having industrial purpose? No, the words ‘manner of manufacture’ arise from theStatute of Monopolies enacted by parliament in 1624 to prevent the abuse of Elizabeth 1st (and her successor James 1st) in, for example, granting letters patent to cronies for common items salt and starch.

As such, it is clear that modern Australian technological developments are tested by a phrase formulated in 1624. In other words, the legislators of the Patents Act intent was not to confine future technological developments by an inflexible criterion, but to allow the courts to develop the law to keep abreast with developments in technology. This is one of the great strengths of the Australian Patents Act.

Well if the Patents Act cannot help us in determining whether something is patentable, let’s turn now to what the courts say.

What the courts say

In modern times, let’s consider first the ‘watershed’ NRDC[6] case. NRDC was visionary in its determination of patentability that it has influenced not only subsequent domestic but also foreign common law too.

In NRDC it was said that:

…a process, to fall within the limits of patentability which the context of the Statute of Monopolies has supplied, must be one that offers some advantage which is material, in the sense that the process belongs to a useful art as distinct from a fine art.

The NRDC case involved spraying crops to result in a weed free tract of land. Various tests for patentability had been propounded before NRCD, one of which was that something was patentable if you could sell it, the so-called ‘vendible product’ test.

NRDC neatly clarified the issue by focussing on what results from the working of the method and not necessarily the embodiment of the invention (i.e. whether the embodiment is patentable).

NRDC was succinctly summarised in CCOM[7], where it was held that something was patentable if it was “a mode or manner of achieving an end result which is an artificially created state of affairs of utility in the field of economic endeavour”.

As a result of NRDC and CCOM we have two pronged test as to whether something is patentable, that is:

- Does the end result have practical application? (i.e. is it distinct from purely mental acts); and

- Does the end result have commercial or industrial applicability? (i.e. is it distinct from pure artistic expression)

If the above two ‘prongs’ are satisfied, then patentability will arise.

It is clear now that the test for patentability should consider the end result of the invention, not the inventionper se, a consideration of the “sausage not the sausage machine”. Such a consideration renders moot any analysis of whether a claim has been “tech washed” for, as is evident from case law, an intangible method or a physical device can both be patentable if they result in something useful (practical application) and vice versa.

Indeed, the impotence of “tech washing” has already been addressed in various foreign decisions including:

- “The prohibition against patenting abstract ideas cannot be circumvented by attempting to limit the use of the formula to a particular technological environment” – Bilski v. Kappos[8]

- “Insignificant post-solution activity will not transform an unpatentable principle into a patentable process” – Diamond v. Diehr[9]

- “it does not necessarily follow…that a business method that is not itself patentable subject matter because it is an abstract idea becomes patentable subject matter merely because it has a practical embodiment or a practical application. In my view, this cannot be a distinguishing test, because it is axiomatic that a business method always has or is intended to have a practical application.” – Amazon 1-click appeal[10]

Furthermore, it is inconsequential as to whether something can be called a “business method” or not. We refer to Grant[11] which, despite Mr Grant’s asset protection method being held to be unpatentable, clarified that:

Mr Grant’s asset protection scheme is not unpatentable because it is a “business method”. Whether the method is properly the subject of letters patent is assessed by applying the principles that have been developed for determining whether a method is a manner of manufacture, irrespective of the area of activity in which the method is to be applied. It has long been accepted that “intellectual information”, a mathematical algorithm, mere working directions and a scheme without effect are not patentable. This claim is “intellectual information”, mere working directions and a scheme. It is necessary that there be some “useful product”, some physical phenomenon or effect resulting from the working of a method for it to be properly the subject of letters patent. That is missing in this case.”

Application of case law

It is clear from the above that something is patentable if the end result has utility. Applying this test, below are examples from case law that were held to be patentable:

- Electrical oscillations – Rantzen’s Application, (1947)

- A weed-free tract of sown land – NRDC

- A fog-free atmosphere – Elton and Leda Chemicals Ld.’s Application, (1957)

- A fire quenched subterranean formation – Cementation Co. Ltd.’s Application, (1945) 62 RPC 151)

- Producing a curve image – IBM (1991)

- Retrieval of graphical characters for assembly of text – CCOM v Jiejing (1994)

- Writing information to a behaviour file – Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity [2001]

The above examples all evidently result in something useful, something having practical (but not necessarily physical) applicability. By contradistinction, below are examples from case law that were held not to be patentable:

- A method of protecting an asset including steps of establishing a trust, making a gift to the trust, making a loan from the trust and securing the loan – Grant

- Hedging losses in one segment of the energy industry by making investments in other segments of that industry – the US Bilski v. Kappos[12]

You’ll agree that these latter cases don’t result in something having practical applicability. For example, how can a ‘protected asset’ have practical applicability?

Turning now to the question of whether a computing device will result in patentability, the decisions of NRCDand CCOM held that the relevant test should consider the end result and not the embodiment. Applying these to a computer implemented method, and using the example of curing rubber from Diamond v. Diehr[13] it is clear that a computer calculating the Arrhenius equation on its own would not be patentable, but applying the computer calculating the Arrhenius equation to curing rubber would. This distinction can be neatly summarised by the following info graphic:

Canadian Amazon 1-click case

While we sit tight and await the outcome of the abovementioned Research Affiliates appeal later this year, it is interesting to note that a similar question of law has already played out through the courts in another country, Canada.

Why should we care about what happened in Canada? Well, firstly, the Canadian Patents Act comprises a definition[14] of an invention, much like our own Act. Therefore similar considerations would apply in considering whether something was patentable. Note that the Canadian and Australian Acts are distinct from those of our European counterparts in implementing the European Patents Convention, which, instead of defining what constitutes and invention, enumerates exclusions to patentability.

Secondly, the practice of the Canadian Patents Office is much like that of our own. The Canadian Patents Office unilaterally narrowed the scope for patentability for business methods, used the ‘substance over form’ approach and excluded computer implementation as being ‘merely incidental’. Sound familiar?

The practice of the Canadian Commissioner resulted in Amazon’s ‘1-click’ invention being refused and being taken on appeal. Amazon’s ‘1-click’ invention related to using cookies to remove an online shoppers need to re-enter credentials during checkout, resulting in a speedy checkout process.

What the Commissioner did in refusing the application was adopt the “form and substance approach” by asserting that a computer was known and was therefore to be excluded (i.e. that the computer is “merely incidental”). The Commissioner then looked at what was left (i.e. the ‘core’ of the invention). The Commissioner said that what was “added” or “discovered” was limited to streamlining the ordering method which was a “business method”. The Commissioner said that since ‘streamlining the ordering method’ was not ‘technical’ it was not patentable.

Amazon appealed[15] the decision to the Federal Court of Canada where Justice Phelan took a dim view of the Commissioners approach, stating that:

The absolute lack of authority in Canada for a “business method exclusion” and the questionable interpretation of legal authorities in support of the Commissioner’s approach to assessing subject matters underline the policy driven nature of her decision. It appears as if this was a “test case” by which to assess this policy, rather than an application of the law to the patent at issue.”

Furthermore, is was reiterated that that there was no “tradition” for the exclusion of “business methods” (thereby agreeing with the abovementioned Grant case).

Justice Phelan also rejected “form and substance approach”, an approach used by the Delegate in Research Affiliates. He reiterated that the claims define the invention which are to be construed in a purposive manner.

The Commissioner appealed the decision but the decision was substantially sustained and Amazon’s patent was eventually granted.

What will be the outcome of Research Affiliates?

As such, on the basis of the Amazon 1-click case, we believe that it will be reaffirmed in the Research Affiliates Appeal that:

- “Business methods” are not unpatentable. The test remains as per NRDC in that something is patentable if it results in something useful having practical applicability; and

- It is improper for the Examiner to disregard features of a claim in assessing patentability in reading out integers from a claim (i.e. computers are “merely incidental”) or referring to the specification (i.e. ‘substance over form’ approach). Indeed, s40 of the Act reiterates that it is the claims that define the invention.

As such, our advice for Australian Patent Applicants is ‘defer and delay’ until such time that our courts provide some clarity as to patentable subject matter. Applicants should defer examination as long as possible and ‘jump out of the reeds’ so to speak once the law has been settled. Applicants may also consider the Innovation Patent system wherein applications are not examined as a matter of course and therefore no determination as to patentability will be made.

When the law has been settled, patent applicants and practitioners should realise that “tech washing” a claim won’t necessarily get the claim across the line. Rather, the proper test, whether the embodiment of the invention is tangible or not, is as per NRDC in whether the working of the claim results in something useful having practical applicability.

Furthermore, patent practitioners should draft claims that specifically result in something useful having practical applicability. Doing so will make it simpler to argue a patentability rejection should on occur during examination by simply referring to the court authorities mentioned above. Considering the abovementionedInvention Pathways case directed to policing compliance during a commercialisation process using a checklist, we suggest that the following exemplary claim may assist in showing the end result (as indicated in underlined text) :

- A computing device for generating invention specific noncompliance notification data, the computing device comprising:

- a processor for processing digital data;

- a memory device for storing digital data including computer program code and being coupled to the processor;

- a data interface for sending and receiving digital data and being coupled to the processor, wherein the processor is controlled by the computer program code to:

- receive, via the data interface, filing date data representing the filing date of a patent application;

- calculate requirement data representing at least one requirement and associated completion date at least in accordance with the filing date data;

- receive, via the data interface, compliance data representing compliance with the at least one requirement;

- … (some more steps here)

- send, via the data interface, noncompliance notification data representing noncompliance with the at least one requirement.

In closing, if you have any questions as to patentability, or are considering patenting a process, software or the like, please contact a Baxter IP Patent Attorney, who can discuss with you strategies to achieve effective protection for your valuable invention.

Footnotes

- National Research Development Corporation v Commissioner of Patents (“NRDC case”) [1959]; CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd [1994]; Welcome Real-Time SA v Catuity Inc [2001] and Grant v Commissioner of Patents [2006]

- 21 July 2010 Invention Pathways Pty Ltd APO 10; 21 October 2010 Iowa Lottery APO 25; 17 December 2010 Research Affiliates, LLC. APO 31; 5 January 2011 First Principles, Inc. APO 1; 11 March 2011 The Proctor & Gamble Company APO 14; 12 July 2011 Myall Australia Pty Ltd v RPL Central Pty Ltd APO 48; 9 August 2011 Discovery Holdings Limited APO 56; 19 August 2011 Network Solutions, LLC APO 65; 28 October 2011 Jumbo Interactive Ltd APO 82; 20 December 2011 Sheng-Ping Fang APO 102; and 17 January 2012 Celgene Corporation APO 12

- Grant v Commissioner of Patents decision, [2006] FCAFC 120

- 2010 Research Affiliates, LLC. APO 31

- https://www.comcourts.gov.au/file/Federal/P/NSD3/2011/actions

- National Research Development Corp (NRDC) v Commissioner of Patents, [1959] HCA 67

- CCOM Pty Ltd v Jiejing Pty Ltd [1994] FCA 1168

- Bilski v. Kappos, 130 S. Ct. 3218, 561 US , 177 L. Ed. 2d 792 (2010)

- Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981)

- The Attorney General of Canada and The Commissioner of Patents v Amazon.com [2011] FCA 328 (24 November 2011)

- Grant v Commissioner of Patents decision, [2006] FCAFC 120

- Bilski v. Kappos, 130 S. Ct. 3218, 561 US , 177 L. Ed. 2d 792 (2010)

- Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981)

- S2 Canadian patents act: “Invention” means any new and useful art, process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement in any art, process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter

- Amazon.Com, Inc. and The Attorney General Of Canada, and the Commissioner Of Patents 2010 FC 1011

Related Services & Resources