Claims and issues in filing chemical, biotech and pharmaceutical patents

Since the awarding of one of the very first modern patents to Samuel Hopkins in 1790 for his potash production method, chemical patents have been used effectively for the benefit of the inventors. What constitutes a chemical patent? Claims in chemical patents may cover the composition of matter (how a substance is used), a product yielded by a process, a particular process, or a novel compound.

Despite the advantages of owning and maintaining a patent portfolio, some people see patents, such as those in the chemical, biotech and pharmaceutical industries, as a way to stifle innovation and solely as a way to make a profit. However, patents are, to a certain extent, considered as rewards to inventors for having contributed to science. How so? In exchange for disclosing the details of the innovation, the IP right becomes in force upon grant. Thus, the specifications in the patents provide background literature for future innovators to use as basis in developing new or improved materials, processes and drugs. Patents are also an incentive to make new and more effective products. Here, we discuss several considerations in filing chemical, biotech and pharmaceutical patents in Australia, such as the types of claims included in the patent application, scope of patentable subject matter, and other considerations.

Some issues of patentable subject matter

Patent attorneys and inventors alike encounter certain issue when preparing their patent applications.

- Patentable subject matter being a manner of manufacture

- Novelty

- Non-obviousness

In certain jurisdictions such as Europe, the European Patent Convention (EPC) provides a statutory exemption to patentability directed to methods of treatments of humans and animals on socio-ethical grounds because certain groups, such as medical practitioners, would directly infringe by application of such treatments, and they would be generally inconvenienced by these patents. However, such exemptions do not apply in Australia and the US.

In Australia, a claim or claims defining the invention needs to be novel (new) at the priority date. Novelty is assessed by comparing the claim and claims with the prior art base, which includes:

- A single publication in any form available anywhere in the world before the earliest priority date of the patent application; and

- A single use (including for ex. public use and public sale) performed anywhere in the world before the earliest priority date of the patent application

Anticipation, or want of novelty, depends on whether all details are made available to the public, i.e. there are ‘clear and unmistakable directions’ in the alleged anticipation, to do what the patentee claims to have invented.

On the issue of inventive step, the Australian High Court has often stated that obviousness means “very plain” – the question is always “is the step taken over the prior art an ‘obvious step’ or an ‘inventive step’”?

Types of chemical claims

In chemical patents, a solution to patentable subject matter can be the claim form. A range of different types of claims may apply. For example:

(i) Markush claim

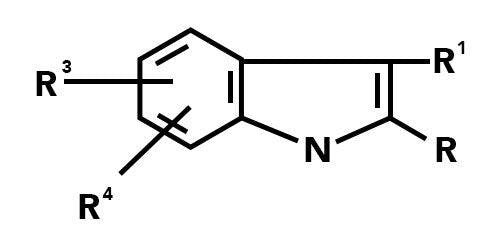

Markush claims Occur where a “significant structural element is shared by all of the alternatives” if the compounds share a common chemical structure that occupies a large portion of their structures, or, if the compounds have in common only a small portion of their structures, the commonly shared structure constitutes a structurally distinctive portion, and this structure or portion leads to a technical contribution in view of existing prior art.”

A typical claim may be as follows:

Novel compounds according to formula (I), wherein R1 is selected from the group consisting of phenyl, pyridyl, thiazolyl, triazinyl, alkylthio, alkoxy, and methyl; R2-R4 are methyl, benzyl, or phenyl.

A benefit of Markush claims is that they provides a format to cover potentially thousands of alternative compounds based on a core structure.

A disadvantage is that the potential scope is so enormous that it is practically impossible to exemplify all notional compounds. Therefore, the Markush claim is likely to face a SECT. 40 ground of objection that the claim is not enabled across its full scope on the basis that the specification does not provide sufficient guidance to produce each and every compound covered by the claim. In addition, all compounds need to meet the requirement of novelty and inventive step.

(ii) First medical use

First medical use occurs in instances where the compound (let’s call it compound A) is known and the invention resides in the discovery that the compound can be used for treating a disease (let’s call the disease ‘disease A’). An acceptable novel claim may be:

- “A drug for treating disease A, comprising compound A.”, or

- “A method of treating a patient suffering from disease A with compound A.”

(iii) Second medical use

Second medical use occurs in instances where compound A per se is known and its use has been known for treating disease A, and the purported invention resides in the use of it for treating disease B. A usual claim may be “A drug for treating disease B, comprising compound A.”

(iv) Swiss type claims

Swiss type claims occur when compound A is not new but its use as a drug is new. A usual claim may be “Use of compound A in manufacturing a drug for disease A.”

Swiss-type claims were developed in jurisdictions (particularly Europe) to:

- avoid patent subject matter exclusions to methods of treatment claims; and

- capture direct infringements of third parties by unauthorised importing, marketing or supplying the generic products for the claimed therapeutic use

The question of scope of Swiss type claims has been problematic in Australia. In order to establish infringement of a typical second medical use claim such as ‘use of substance X for the treatment of condition Y’, it is necessary to show that a person has used the method or at least played a role in another person’s use of the method.

The Federal Court decision in Apotex v ICOS Corporation (No. 3) [2018] FCA 1204 confirmed that a Swiss type claim of the format ‘the use of substance X in the manufacture of a medicament for the treatment of condition Y’ is likely to result in a physical product.

On this basis, products imported into Australia manufactured overseas using the patented method would infringe Swiss type claims.

Indigenous knowledge

Protection of indigenous knowledge and resources has been a major concern in the context of local and international patent laws. Pharmaceutical companies, for example, are known to have obtained monopoly control of pharmaceuticals through patent rights, as well as flow on economic returns, from inventions that have benefitted or derived from indigenous knowhow. Legal protections of indigenous knowledge in Australia is therefore recognising that indigenous people possess ”special knowledge about biological resources.”

Extension of term of pharmaceutical patents

Often in the case with pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical patents, a substantial portion of the 20-year term of the patent is consumed before a patent owner can start to derive an economic return on R&D investment in developing a new pharmaceutical, with the process of obtaining regulatory and marketing approval, not to mention a substantial period usually observed in conducting field and/or clinical trial work. Therefore, in some instances, a pharmaceutical patent owner may have a shorter effective patent term within which to obtain full commercial advantage and indeed recover investment costs. Thankfully, the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) provides an opportunity to obtain an extension of the patent term. Certain minimum requirements, timing of application and calculation of term are prescribed in SECT. 70 of the Act. An extension of term is capped at a maximum of five years.

If you need help drafting your patent claims and filing your patent applications, feel free to contact our chemical, biological and pharmaceutical patent experts.